The Mysterious Allure of Caves

Gnostics say that experience, or the absorbing of what you see and experience is far more important than formal study and education. It has something to do with nature–being close to the earth–and the innate wisdom of intuition that has all but been purged from our senses

since birth. It is the musky scent of Sophia and the deep feminine, of damp soil, dark caves and wombs, and of the fertility rites of the old pagan ways “When God was a Woman.“

When I was a teenager a few of my friends and I would occasionally take the latest feminine objects of our desires to a cave system called the Tongue River cave west of Dayton, Wyoming, to hopefully seduce them, for there is something sensual–even erotic–about penetrating deep into the dark, damp, yet pleasantly pungent, atmosphere of a cavern where even the most prissy and proper of our young lady friends soon succumbed to the passion of her natural sensuality.

We didn’t understand such things then, but the cave was the perfect metaphor for those girls’ own private caverns that were the ultimate objects of our amateur spelunking expeditions. I suppose we naively thought that the ease with which we were able to lure them into having our way with them had more to do with our significant masculine charms and seductive powers than with where we were. But even though we didn’t understand, inherently we all knew, no doubt, that our successful missions inside the cave had something more to do with the feminine way, but who wants to critique success.

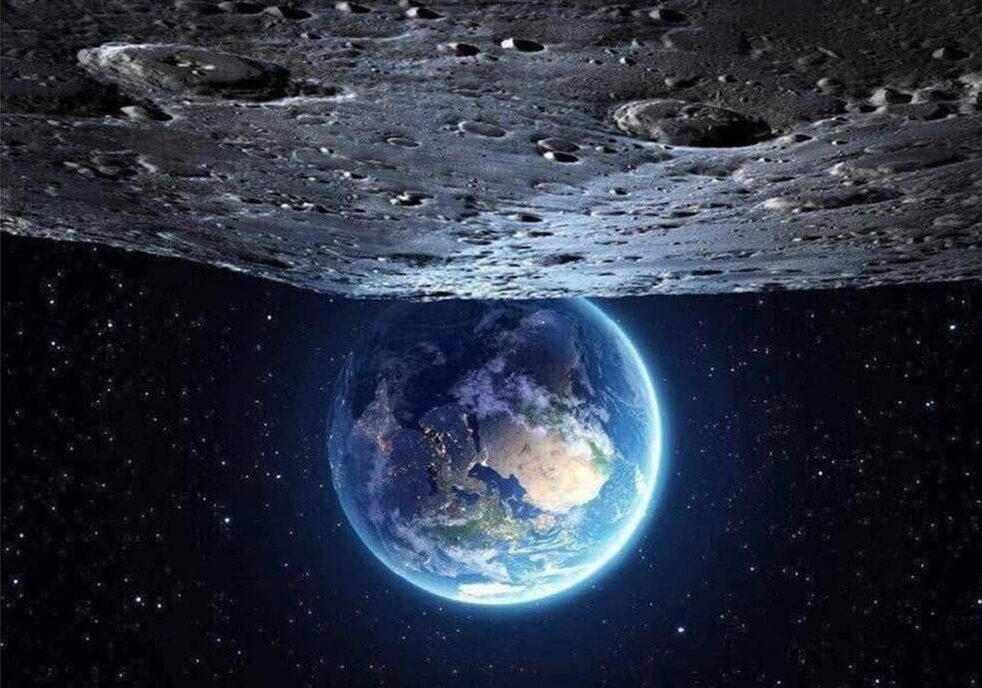

Paulo Coelho, recently contemplating the mysteries of caves on his blog, wrote: “Caverns symbolize the secret access to the underworld. They are the eldest places of cult that humanity knows. During the Ice Age, it is believed that men already regarded caverns as being from another world. Cavern[s] are omnipresent in virtually all traditional cultures. The Aztecs for instance believed that caverns were the creators of the world, whilst the Mayas linked caverns with the goddess of the moon – linking then the earth, the waters and fertility in the same symbolic ensemble. The cavern has also a central place in Plato’s philosophy : men are considered to be inside the cavern, only being able to watch the shadows of Ideas. It is only progressively, through initiation, that they will be able to come out of the cavern and look upon the Truth thanks to the light of the Sun. In Christianity, it is believed that the John the Evangelist had his vision of The Apocalypse in a cavern in Patmos. Bernadette has also the vision of the Immaculate Conception in a grotto in Lourdes.”

Plato’s thoughts on caverns are truly gnostic in nature, and the Mayans linking of caverns to the “goddess of the moon” and fertility is hardly unique to their society. Such pagan feminine spirituality and sexuality rites go back to Sumerian times and further – perhaps 35 thousand years or more. The symbolic path of caverns to the underworld ties the mythical rape and abduction into the underworld of Korè Persephone by Pluto to the Eleusinian Mysteries that according to Plato and other philosophers allowed mankind to elevate above the human sphere into the divine and assured his redemption by making him a god, conferring immortality upon him (Nilson), and to lead us back [from the underworld] to the principles from which we descended – . . . the perfect enjoyment of spiritual good (Plato).

But it was not always to seduce girls that my friends and I explored the Tongue River cave. In fact, the cave held mysteries of the unknown that enticed us to repeatedly go back to the depths of it (more than a mile to a place where an underground stream pools against a sudden narrowing of the cave walls – a point we dared not venture beyond, for it would require going underwater for who knows how far into an unknown part of the world). We often talked about trying, but, I’m sure, never very seriously. I’ve always wondered what is beyond that pool and whether anyone has ever had the courage to try to find out.

The last time I was in the cave, we’d ventured all the way back to that pool. There were four of us as I remember– three of my closest friends and me. To reach the stream level of the cave, one must descend about 60 or 70 feet vertically (80 or 90 feet obliquely) through a huge shaft-like room we called “the corkscrew.” It is by far the most dangerous area of the Tongue River cavern complex. Though we’d descended and ascended the corkscrew several times over the years that we’d visited the cave, this time we all somehow strangely became disoriented and none of us could find the exit from the corkscrew far above at the top of the giant room. Eventually we split up, allowing us to search individually for the exit opening in a more efficient, but more dangerous, way.

Irritated over our dilemma, I remember feeling frustration over the fact that we seemed to be lost in a place we’d navigated easily so many times before. Worried about time, for none of us had an inexhaustible supply of light, I began to scramble up what I believed was the northwest side of the corkscrew, clinging to the jumble of fallen sandstone or granite boulders that made the climb possible. As I neared the top of the enormous room, I saw the exit opening just ten feet above, and I remember the joy I felt at having spotted it. Excited, I carelessly turned myself away from a spire of rock that I was clinging to to call out to the others that I’d found the opening, but I never got the words out of my mouth, for I lost my hand- and foot- holds , falling backward from the ledge.

As I fell, I remember thinking something like, well, I’ve had a good life, instantly resigning myself to certain death. I did not scream, and I actually felt a certain peace as I fell, almost like floating through the air rather than falling, well aware of the rocky floor at the base of the room near the meandering little stream. I recall painlessly bouncing off rocks along the cavern wall at least twice during my descent, which seemed to take an inordinately long time. I thought I heard screaming, but knew it wasn’t my own voice. Finally, I slammed hard against the floor of the corkscrew.

To this day I don’t know if I lost consciousness, nor do I know how long it took for the others to reach me, or even, initially, if I was alive. But I do remember a light shining in my face, the glare making me squint, trying to figure out who was behind the light. And then I heard the voice behind the light, and recognized the sound of it, and decided I was probably alive.

There was no pain, I knew that, except for a dull throb in my hip – I don’t recall which one. As I collected my wits, I realized I seemed to be unhurt. There were no splintered bones, no smashed skull, no bloody mess – not much of anything out of the ordinary so far as I could tell. The others gathered around me as I sat up, as amazed as I was that I was alive and unhurt. We all exchanged exclamations and thank-gods until the initial shock of the event began to wear off.

On my feet, I dusted myself off, and adjusted my cowboy hat, which inexplicably remained perched on my head, though I was aware I’d made multiple full body revolutions during the fall. Taking stock, I realized one of my tennis shoes was missing; so was my flashlight; so was my wallet; and so were some keys and coins in a front pocket of my Levi’s. We searched for these various items for quite a while, but we never found any of them. Finally, we gave up and began to ascend the corkscrew slowly and carefully in the direction that I’d recently so spectacularly come down from.

We made it out of the corkscrew and eventually out of the cave without further trouble, descended the steep trail to the old bridge across the Tongue River, and made our way downstream to our vehicle at the trailhead.

The fall was like falling from a five or six-story building, and though I’d luckily landed in a small drift of soft sand covering the rocky floor of the cave near the meandering little stream, where small pure-white trout often reflected off our lights, To this day, I am not sure that I actually lived through that fall. Over the years I’ve been haunted at times by an unsettling awareness that, though I died from that fall, life has gone on as if I hadn’t. Sometimes the feeling is so intense that it is almost unbearable–consisting of an unnerving, almost panicky, sense that I’m not where I’m supposed to be.

Other than the small bruise on my hip, though I distinctly remember smashing into and bouncing off those sidling rocks during my dream-like descent and then crashing so hard against the sand and rocks on the floor of the cave that I seem to still remember the crushing sound of the impact, I walked away from that death-defying fall minus only a billfold, a tennis shoe, a flashlight, some keys, and pocket change. The almost total lack of injury or even pain is what puzzles me so, perhaps causing the admittedly intermittent but horrifying sensation that I died that day, at about 19 years of age, on the floor of the corkscrew in the Tongue River cave. It’s not a feeling that I cheated death; it’s a feeling that I died but lived anyway, and that I’m not where I’m supposed to be. There is no way to explain the sensation of it any clearer than that.

So the end result of all these mindful struggles about the validity of my own existence, or lack of it–whichever the case may be–has led me to the inevitable concept that all things, organic and inorganic, exist in side-by-side parallel universes that we are not normally supposed to be able to discern other than the one we consciously exist in. To me, the concept is compatible with the metaphorical cavern supposition of philosophers like Plato, Nilson, and others.

I’ve wished for many long years that I could better see or otherwise pass through the diaphanous veils of my soul from this world that I’m existing in into one or more of those that I have the uneasy feeling I should be in. I believe it is possible for our transcendent soul, and possibly even our immanent physical being, to cross over into these parallel worlds through a warp or a hole in the space /time continuum. The Hopi and related American Indian tribes like the Anasazi and Navajo call these holes sipapu. There is abundant evidence that such holes, openings that I usually refer to in my writing as cosmic vortexes (vortices), actually could exist according to the theories of quantum physics and metaphysics.

My books are all intrinsically linked to that mysterious fall in that cave so many years ago, hence the anthological title “Sophy’s Way: Parallel Worlds of the Moon.” ~llaw